Teamwork and Innovation: The Great Sled Run

“What if we built a sled run from behind the Rock All-the-Way Down?!”

I don’t remember who said it, but it was an idea that had immediate and universal acceptance.

We weren’t saying “Oh Wow!” then, or even “Wicked Awesome!” But whatever we said there was total enthusiastic commitment to this idea.

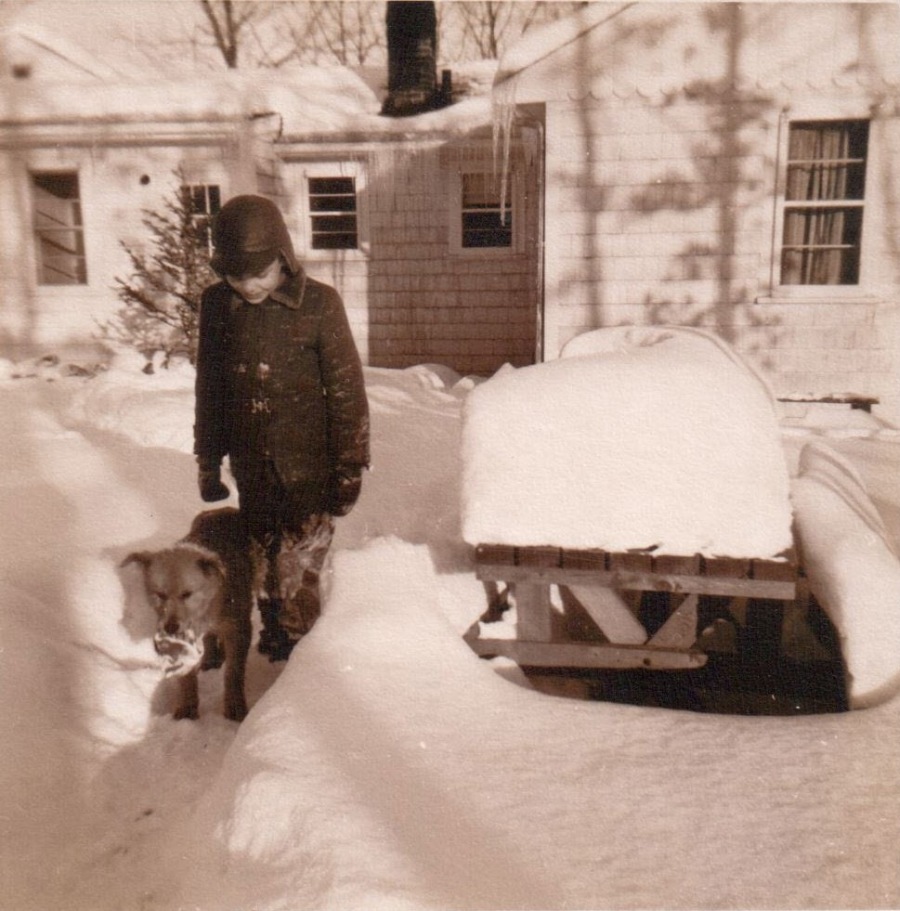

The snow was perfect; it was probably about 26 degrees Fahrenheit. I say that because the snow had moisture, not the fly-away powder that skiers crave. It was perfect snowball, snowman snow. It was packable, but not too wet.

The Initial Prototype

The Cooper’s had a four passenger wooden toboggan. That was to be our steam-roller for the run. We walked mid-way up the hill and rode down, snowflakes stinging our eyes, scarves flapping in the face of the person behind. We took turns sitting in the front, packing the snow down.

Then we tried the sleds. The sleds were all a version of Flexible Flyer Junior racer. The runners did not have the rear ‘V’-shaped runner that avoided poking your eye out if you rear ended another sled. We had all heard the story of “someone’s cousin who crashed into his sister’s sled and put a runner shaped hole in his cheek.” The story was probably an early version of an urban myth, but it kept us from following too close.

We belly-flopped on the sleds at the top of our abbreviated run and headed down.

“Too slow” exclaimed David when we were all down.

“Yeah the runners are still cutting too deep into the snow” I agreed.

“My sled top’s dragging the top of the snow,” said John. John was a year and a half older, and taller and may have weighed a little more.

“More packing!” We all said in unison.

Stomp, stomp, pound, pound. Stomp, stomp, pound, pound. We worked hard on our short little prototype run for about a half hour. Then we tried it again: walking up the hill at the side of the run so as not to mar the even surface with our galoshes. Then we each made the running start, the belly-flop on the top of the sled (Oof!), and hurtled down the run which was about a third of the hill, maybe 40 yards.

We hooped and hollered. The run was a lot faster. We were running into the deep snow at the end of the run, sliding off our sleds as our bodies wanted to keep going. Even though our faces got ground into the snow, we all ended our runs laughing uncontrollably.

“We gotta make it longer.”

The Drive for Distance

We expanded the run up the hill first to the base of Cooper’s Rock. We used the same process, first toboggan, then stomp, stomp, stomp, pound, pound, pound. We tried the sleds.

This time we had our first injury. When we got speeding to the bottom, David slid off his sled with such force, he nosed deep into the snow and hit his head on a rock. “OW!”

“This is Ma’s garden,” said John. “She’s not gonna like it if we dig up her garden. “ John was always the responsible one.

“The run needs to turn left here.”

“That’s the Boyington’s yard”

“Billy’s not gonna be outside in this; it’s over his head.” Billy Boyington was three. We kids always laughed at how overprotective his mother was. “His mother wants to put him in a football helmet to play outside. She’s not gonna let him go out if he needs a snorkel to breathe.”

It was decided. The run would go left into the Boynton yard and the right and down the hill towards Lincoln Street. First the toboggan, then stomp, stomp, stomp, pound, pound, pound.

The ‘S’ curve proved tricky. The first sled down the hill went horizontal at the left hand turn. Sled and rider, me, separated. I traveled about 5 yards further than the sled. “Oooooh.”

John and David came running down the hill. It was determined that Alan was OK. Then we set to work on a banked curve. (Where did 8-10 year olds hear about a banked curve? I don’t know; maybe we just sort of figured it out.) We shoveled a high mound behind the curve, tried it from mid-hill, and kept at it till it worked. Then we worked on the right turn the other half of the ‘S.’

We kept trying this from various hill heights until we got it to work.

First Safety Issue

Then it came time to try the run, still starting at the bottom of the Rock, but running all the way through the Boynton’s yard. This time, David was the experimental tester.

Around this time, the snow had stopped, and word had got out in the neighborhood that ”there was a sled run at Cooper’s.” The boy-pack began to show up. First Billy and Don Lunday, then Charlie and Dickie Arbene. When David made his run, he had an audience lining the track, each holding his sled.

As his sled screamed down the hill, people were cheering. It sounded like the riders sound on an amusement ride. When he hit the ‘S’ “oooooOOOOOHooooooOHoooo” it was like the “wave” at the SuperBowl.

Even with the natural slowdown due to the ‘S,’ David was going really fast. Then the crowd went “OOHHHH NOOOOOO.” David and his sled sped down to the end of the Boyington’s yard, over the slight embankment and was airborne right onto Lincoln Street. I can still hear the clatter that the sled made and the “ooumpf” that was the air being pushed out of David’s chest.

Lincoln Street was a pretty busy street. In good weather cars sometimes sped along at 40 miles an hour. We were all warned by our parents to “Stay out of the street.” Luckily, no cars were coming. The street had been plowed once, but not very well and it was empty. David scrambled back to the Boynton’s yard.

“We gotta do something to stop.”

“You could roll off the sled.”

“Too fast”

“We could cut out the last leg in the Boyington’s yard.”

“Aw, nah, that’s half the fun.”

“Let’s build a backstop,” said David.

And so we did. The entire boy-pack, directed by David, the “engineer,” built a curved wall almost 6 feet high out of snow. Your sled came in low on the right and the wall carried you around to the left and ultimately pointed you back up the hill. It worked magically.

With the backstop, it didn’t seem to matter how fast you were going. Some dragged their feet after the ‘S,’ but the daredevils, David, Charlie and I, pushed the limit every time.

The Need for Speed

We extended the run up the back of Cooper’s Rock. It was now about 200 yards long and about a 30% grade. We began to time the runs. The sledder would yell when he started and we’d time the run on with the sweep second hand on John’s Timex watch. I don’t remember how long it took, just that when I was sledding it felt very fast.

Someone, (I don’t remember who) suggested that we should ice the track. I remember carrying bowls of water up and down the run and sprinkling water on where the sled runners hit. We ran a couple of runs – faster.

Then it got dark. The boy-pack dispersed. Someone managed to talk Elizabeth into letting us use the hose. That was probably John; we often let the “responsible one” talk to the adults.

We wet down as much of the run as we could reach with the hose and retired for the night.

The Second Safety Issue

The next day the boy-pack was back early. The iced run was demonically fast. The ice made the run trickier. We built up the banks on the ‘S’ curve and the backstop a little higher in response.

We had long since stopped timing the runs. Everyone just wanted to get down and then climb back to the top so they could go again.

We also weren’t following our rules about how long you had to wait between sledders anymore. The net effect was that sleds were speeding into the Boyington yard one after another, a sort of Indy 500 on snow.

It definitely wasn’t fair to young Billy. He probably wanted nothing more than to play in the snow in his own yard with the big kids. He got dressed in his snow suit and came outside.

Suddenly, a woman screamed.

I can still remember Kay Boyington running out of the house without a coat, with panic on her face. Billy was on the ground halfway between her back door and the ‘S’ curve.

He got up looking very frightened. He probably wondered why his Mom was screaming and crying.

Poor kid was just making a snow angel.

In retrospect, Mrs. Boyington was frightened into hysteria, but we were 8, what did we know.

“YOU BOYS STOP THIS SLEDDING RIGHT NOW! BILLY COULD HAVE BEEN KILLED!”

We stopped. I think most of us realized that even though Billy wasn’t in danger at that moment, it was very dangerous. What if. . . ?

Someone talked with Mrs. Boyington (Elizabeth? John?). Mrs. Boynton seemed to calm down a lot after that. After a while, someone, probably John, put Billy Boyington on a sled and let him have a couple little rides on the bottom part of the run. I remember him giggling like a 2 year old.

The boy-pack had a few more runs after Billy went inside, this time with guards posted so no one would get hit. And the day ended with some more hot chocolate with marshmallows and lots of memories of “the great sled run.”

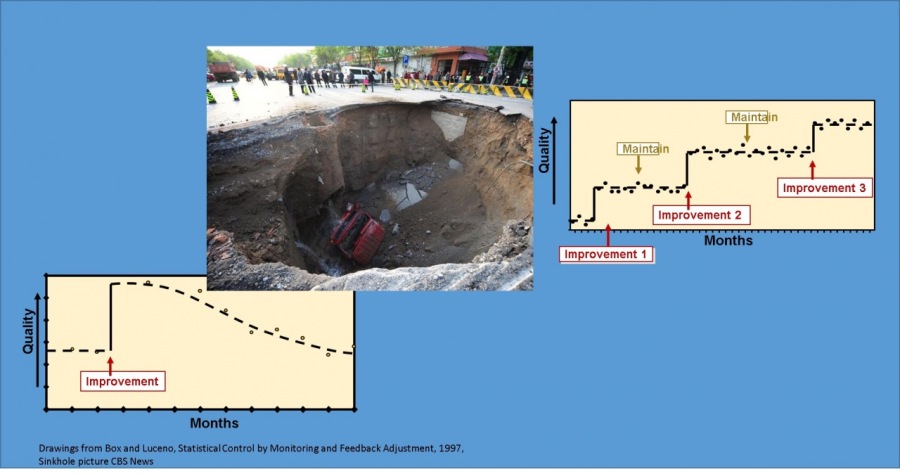

The great sled run is a wonderful, and sobering, childhood memory. These days I help people inside of companies implement innovation and continuous improvement initiatives. There are a few similarities between this story and successes in my work:

- Total Enthusiastic Commitment to the Idea – for us it was spontaneous –“a great sled run.” In my work, this commitment often takes time to build, talking through every opportunity and potential outcome with a participative process.

- Team and teamwork – David and John Cooper and I were the “core team” for this endeavor. We knew each other well (and played together all the time.) It made the planning and building go faster. When the boy-pack (“extended team”) arrived, everybody just pitched in. We all wanted the same thing (“the great sled run”) and we were used to working with each other, (“shared goals, collective work product, and agreed working approach”). In my work this also takes time to build, but the principles are the same.

- Shifting Leadership Roles – as documented by Wilfred Bion, in small teams (3-7 members) the leadership role shifts to the most competent for the task. David, built the backstop because he had the vision based upon clattering onto Lincoln Street; John, the “responsible one” asked his mother for the hose.” I frequently tell my clients -“Small team – large stakeholder network” in order to capitalize on this efficient leadership process.

- Try-it-Fix-it-Try-it Again – We boys fell into a pattern of trying something in a small prototype first, (“abbreviated sled run”) and fixed problems as they arose (the run packing, ‘S’ curve banking and backstop). When teams in innovation and continuous improvement work well, they adopt this experimental mindset; when they get stuck in “analysis paralysis” things project cycle time slows to a crawl.

- Metrics and Measurement – Truthfully, we spent very little of the two days in this story staring at the red sweep second hand on John’s Timex. Most of our measures of speed were based upon “feel.” In my work, how you measure success (results metrics), how you measure if you’re on track (process metrics) and how you collect reliable data about those (measurement) are critical to success.

- Safety and thinking through unintended consequences – for the Cooper boys, the boy-pack and me, this memory of two fun days is tempered by what might have gone wrong. In my innovation and improvement work, safety is always analyzed and there is always a step to anticipate unintended consequences.

Articles from Alan Culler

View blog

Continuous Improvement (CI) is a discipline that has been around in the United States (at least) sin ...

“What problem are we trying to solve?” is a question that can be delivered dripping with withering M ...

“But we just redid our comp ratios.” · “Look, I don’t care when you did them, I’m telling you your c ...

You may be interested in these jobs

-

Line Cook

4 days ago

The Shenandoah Club Roanoke, United StatesJob Description · Job DescriptionWe are looking for someone with a passion for food and strong time management abilities who can provide our clients with an exceptional dining experience. Our restaurant is busy, and we need a competent and experienced line cook who can ensure tha ...

-

Hospital Cooks/Ambassadors/Utility Associates

15 hours ago

HHS Biloxi, United States** Hospital Cooks/Ambassadors/Utility Associates - Biloxi, MS - 1286** · **Job Category****:** Culinary and Nutrition Services **Requisition Number****:** HOSPI05518 Showing 1 location **Job Details** · **Description** · **HHS Culinary Services** · HHS Culinary began as a sol ...

-

Senior Project Director

6 days ago

ATI Restoration Sacramento, United States Full timeJob Description · Job Summary · The Senior Project Director position is responsible for managing and coordinating projects of all sizes and complexities through all phases of design, permitting and construction. Senior Project Directors also provide leadership for site Project ...

Comments

Alan Culler

7 years ago #3

Franci\ud83d\udc1dEugenia Hoffman Thanks Sorry for the typo in your name last time. I appreciate your support

Alan Culler

7 years ago #2

Sorry for the typo on your name, @Franci Eugenia Hoffman I appreciate your support

Alan Culler

7 years ago #1

Thanks Franco I appreciate your support